IV site management

IV site solutions to secure and protect

Your focus is delivering compassionate care to your patients. Our focus is providing you with easy-to-use solutions that help make it possible.

Preventable complications of intravenous (IV) catheters like infections, dislodgment and skin damage put your patients at risk for discomfort and pain, prolonged hospital stays and even death.

Our portfolio of innovative products, including disinfecting caps and IV dressings, can help you protect every IV catheter from insertion to removal. These evidence-based products can help prevent costly complications, improve patient satisfaction and help you deliver what’s most important – compassionate care.

Help reduce the risk of bloodstream infections at all access points

IV therapy is a critical and fundamental part of patient care. While infusion therapy is a common way to deliver fluids and other types of medications, it comes with risks.

In fact, catheter-associated bloodstream infections (CABSIs) can occur at the time of the initial insertion or anytime throughout the duration of intravenous access — creating the potential for longer hospital stays¹⁻⁵, increased care costs²,⁷ and higher patient mortality.⁶

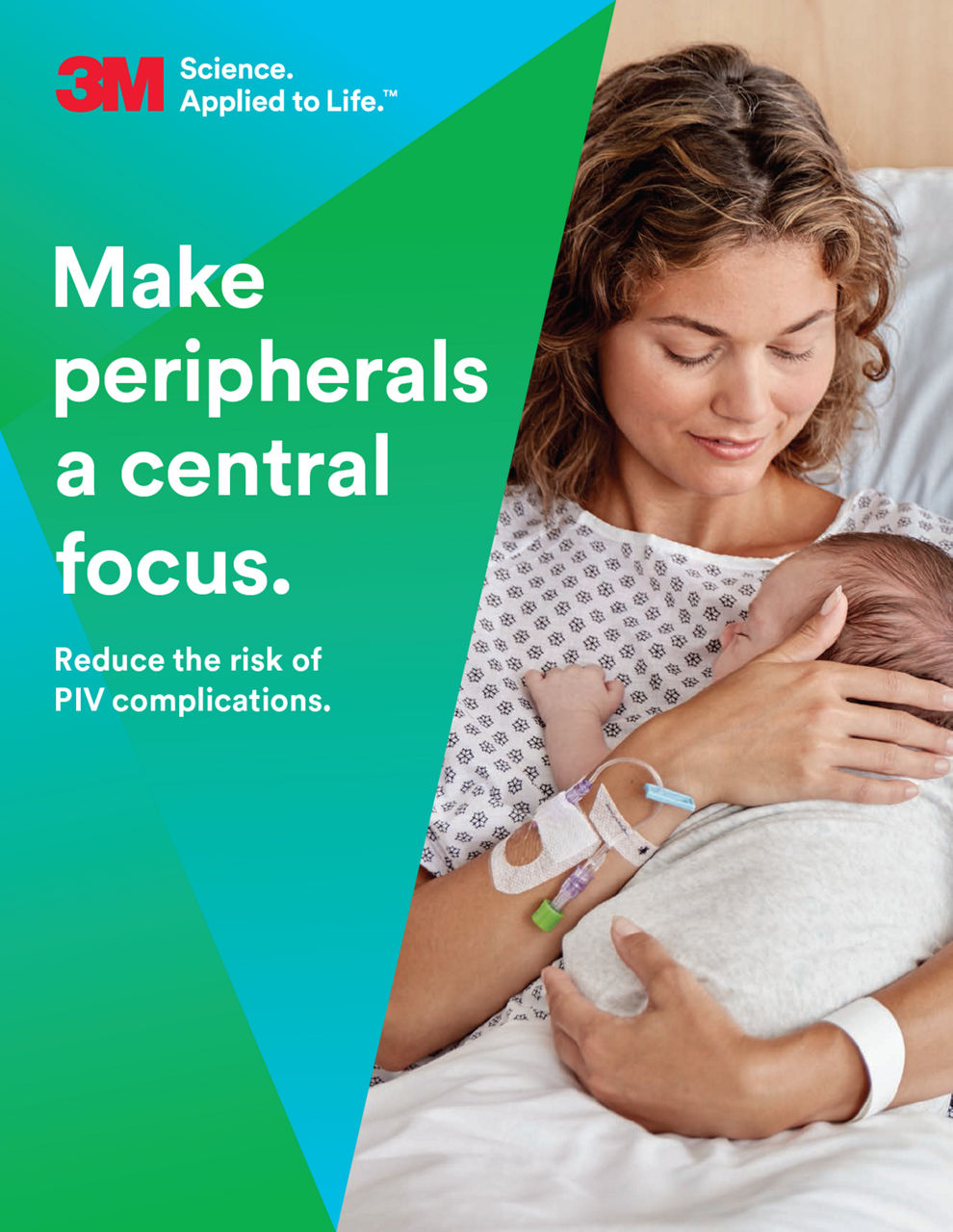

Make peripheral IVs a central focus

Peripheral intravenous catheters (PIVCs, PVCs and PIVs) are some of the most frequently used vascular access devices in healthcare settings, with 60% – 90% of hospitalized patients requiring an IV during their stay.8 However, while placing a PIVC is one of the most common invasive medical procedures performed worldwide,8 it can lead to complications, patient anxiety and dissatisfaction, as well as nurse anxiety.

Many studies point to why PIVCs should be at the center — not the periphery — of initiatives to prevent catheter-related bloodstream infections (CRBSI), reduce clinical cost and improve patient outcomes.

PIVCs are often considered a low-risk procedure; however:

Resources to help prevent PIV complications

Find educational materials to help you address peripheral IV needs and improve outcomes.

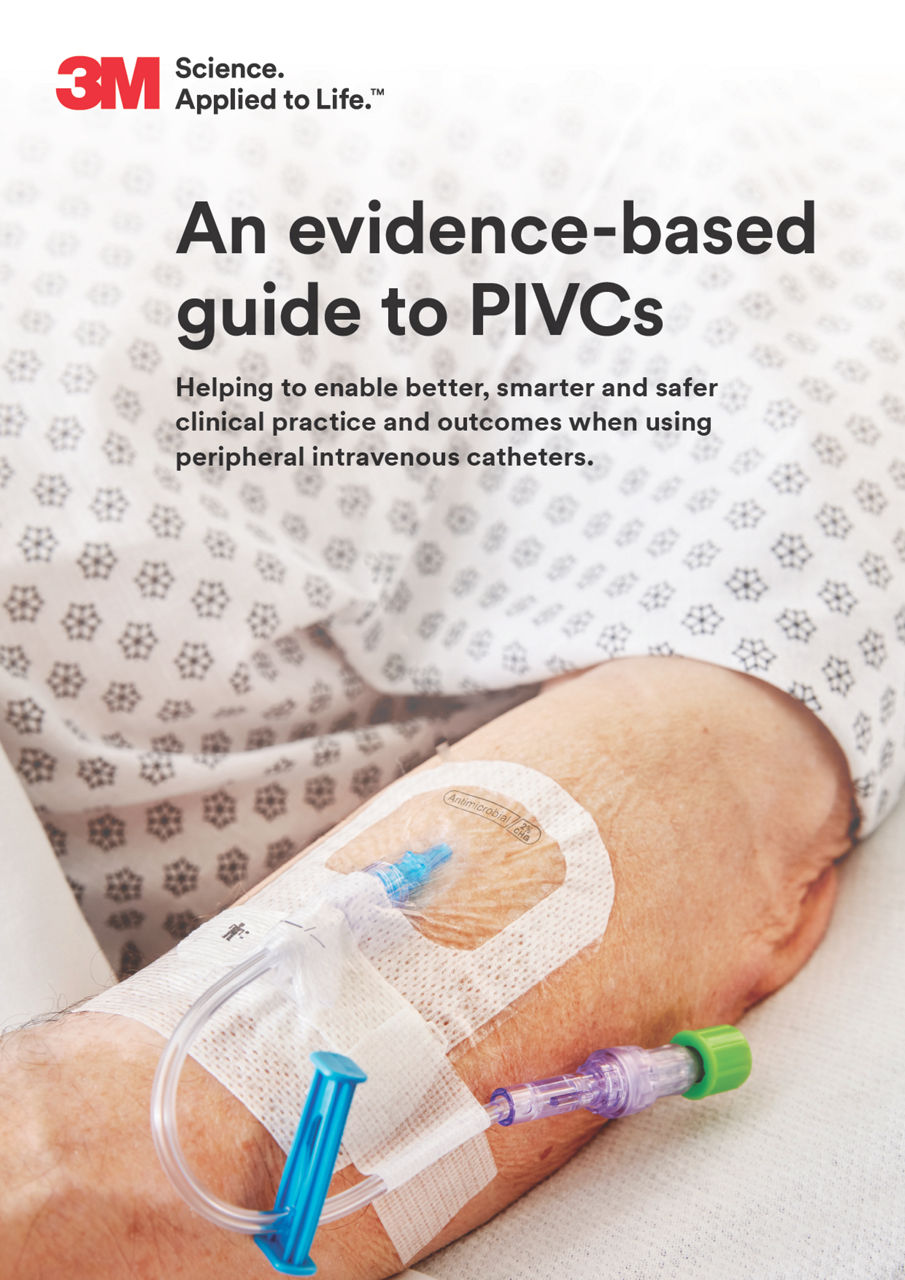

Antimicrobial protection and catheter securement

Organisms on the skin gain access to the bloodstream or via migration through the inner catheter lumen through the catheter port (intraluminal contamination); both important routes of catheter-related bloodstream infections.12

Know your patients are protected from bloodstream infections. Choose from our range of antimicrobial solutions to defend against extraluminal and intraluminal bloodstream infections.

Protect every line, every time

The right solutions are an integral part of your overall infection prevention plan. That’s why we’ve designed proven products to help protect every catheter type and every access point at every step of the treatment journey.

Choose from our family of antimicrobial Tegaderm dressings and Curos disinfecting port protectors to help reduce the risk of complications at all IV access points.

How to use IV site management solutions

We’re committed to providing ongoing training and support to help you improve clinical outcomes. That’s why we offer resources to help you learn how to use our vascular access products, including Curos disinfecting caps and Tegaderm IV dressings.

Resources

Additional solutions to help prepare, secure and protect patients

References:

- Maki D, Mermel L: Infections due to infusion therapy. In Hospital Infections, edn 4.Edited by Bennett JV, Brachman PS. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1998:689–724..

- CDC Vital Signs: Making health care safer: Reducing bloodstream infections. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/pdf/2011-03-vitalsigns.pdf (PDF, 2.75 MB) Published March, 2011. Accessed June 18, 2017.

- Blot SI, Depuydt P, Annemans L, Benoit D, Hoste E, De Waele JJ, Decruyenaere J, Vogelaers D, Colardyn F, Vandewoude KH. Clinical and economic outcomes in critically ill patients with nosocomial catheter-related bloodstream infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2005 Dec 1;41(11):1591-1598.

- Zimlichman E, Henderson D, et al. Health Care–Associated Infections: A Meta-analysis of Costs and Financial Impact on the US Health Care System. JAMA Intern Med. 2013 Dec 9-23;173(22):2039-2046. doi: 10.1001/ jamainternmed.2013.9763.

- Scheithauer S, Lewalter K, Schröder J, et al. Reduction of central venous line-associated bloodstream infection rates by using a chlorhexidine-containing dressing. Infection. 2014;42(1):155-9.

- Center for Disease Control (2005). Vital Signs: Making Health Care Safer. Accessed 7/29/2019 https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/pdf/2011-03-vitalsigns.pdf (PDF, 2.75 MB).

- Zimlichman E, Henderson D, Tamir O, et al. Health care-associated infections: A meta-analysis of costs and financial impact on the US health care system. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(22):2039-2046.

- Helm RE, Klausner JD, Klemperer JD, Flint LM, Huang E. Accepted but unacceptable: Peripheral IV catheter failure. J Infus Nurs. 2015;38(3):189-203. doi:10.1097/NAN.0000000000000100.

- Mermel L. Short-term peripheral venous catheter-related bloodstream infections: A systematic review. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65(10):1757-1762. doi:10.1093/cid/cix562.

- Saliba P, Hornero A, Cuervo G, et al. Mortality risk factors among non-ICU patients with nosocomial vascular catheter-related bloodstream infections: A prospective cohort study. J Hosp Infect. 2018;99(1):48-54. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2017.11.002.

- Buetti N, Abbas M, Pittet D, et al. Comparison of routine replacement with clinically indicated replacement of peripheral intravenous catheters. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(11):1471-1478. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.5345.

- Mermel L.A. 2011. What Is The Predominant Source of Intravascular Catheter Infections?ClinicalInfectious Diseases 52(2):211–212;DOI: 10.1093/cid/ciq108.

- 3M Data on File. EM -05 -014960.

![3M™ Skin and Nasal Antiseptic (Povidone Iodine Solution 5% w/ w[0.5% available iodine] USP) Patient Preoperative Skin Preparation](https://s7d9.scene7.com/is/image/mmmspinco/skin_nasal_anti_pkg15_cmyk?wid=800&hei=600)